Conducting Observational Research for Your Business

In previous sections, we’ve discussed various forms of primary market research: research that draws information directly from prospects and customers (as opposed to secondary research, which entails analysing data that’s already been gathered about them). We’ve looked at market research surveys, in-depth interviews, and focus groups. But there’s one more—very broad—set of primary market research techniques available, all of which fall into the category of observational research.

As we’ve discussed, new technologies have transformed how surveys, interviews and focus groups are conducted. Surveys can now be distributed through multiple channels (email, social media, QR code, SMS); and a wealth of online survey platforms can analyse the data for you. Interviews and focus groups can be conducted over online communication platforms and recorded with digital technologies.

Observational research, however, is evolving more quickly than these other market research strategies. Sure, it still includes watching how consumers move through your brick-and-mortar store. But consumers are now leaving a wake of digital information behind their every move—intelligence that can be easily collected, analysed, and swiftly acted upon. What’s more, the data that observational research offers is often more reliable than the data you’ll get through other forms of primary research. That’s because it rests on what consumers really do… not on what they claim to do.

What is Observational Research in Marketing?

Observational research is the wide-ranging set of methods businesses use to collect information by directly or indirectly “watching” consumers act in natural (and sometimes planned) environments. As such, it’s used primarily in B2C contexts. What observational research ultimately offers is behavioural data… but it measures behaviour directly, rather than relying on consumers’ (sometimes inaccurate) self-reporting. While the subject of observational research might know that data is being collected, they aren’t explicitly involved in collecting it (by filling out survey answers, for example). Often, in fact, there’s no interaction whatsoever—which is why it can be one of the more unobtrusive market research methods out there.

The “observer” takes one of three forms: human, software, or mechanical device. Human observation may be as simple as walking into a brick-and-mortar store and watching consumers pick up your product and your competitor’s product and compare them. Online observation includes tracking devices and web metrics to map user and consumer behaviour; Google Analytics and heatmaps fall into this category. Mechanical observation entails the use of devices—such as cameras or footfall counters—that track consumer behaviour in the non-virtual world.

You’ll note that some of these techniques are more sophisticated than others; and their availability may depend upon your financial resources. But the field is vast enough to support sole proprietorships and enterprises alike.

Observational Research Methods

Here are some methods to consider when deciding what “observation” will mean for your market research question:

- Natural v. contrived observation. In natural observation, subjects are studied in “real life” circumstances and environments. They may or may not know that they’re being observed. In contrived observation, subjects are studied in controlled settings (research labs, for example), and know that they’re being observed. While natural observation can be time-consuming, it often produces better results: Unnatural settings and awareness of observation (the Hawthorne effect) can both alter subjects’ behaviour.

- Direct v. indirect observation. In direct observation, researchers watch subjects as the behaviour is occurring (how many consumers purchase drinks at an event, for example). Indirect observation examines the results of the behaviour, rather than the behaviour itself (receipts for drink sales or the number of empty cups in nearby trash cans).

- Disguised v. open observation. In disguised (or covert) observation, the subject doesn’t know they’re being observed: Think hidden cameras, one-way mirrors, or online tracking. In open (or overt) observation, they do While the latter runs the risk of altering consumer behaviour, it also allows researchers to interact with consumers during or after the study—in effect creating a hybrid of observational research and in-depth interviews.

- Structured v. unstructured observation. In structured observation, researchers clearly define what behaviours will be observed, and the study focuses on that set of predefined, pre-categorised behaviours. In unstructured observation, researchers attempt to capture everything: typical and divergent behaviours, contextual details, and so on. While the “subject” of observation is less defined in unstructured observation, it allows you to better perceive the unexpected. (And believe us when we say… consumers will surprise you.)

Pros and Cons of Observational Research

We mentioned some advantages and disadvantages of the above methods. But there are some pros and cons that many observational techniques share in common; and if you’re wondering whether these approaches are right for you, they’re worth considering.

Advantages of Observational Research:

- Humans often say one thing, but do another: Consumers may not understand their motivations very well, or can’t be certain about how they’d react in a situation until they’re actually faced with it. What’s more, while other forms of primary research leave room for recall error (respondents may not remember the factors that contributed to a purchase decision, for example), observational research collects information as the action is taking place—so nothing gets lost in the time gap. In other words, observational research can offer a more accurate reflection of “the truth.”

- There are certain types of questions that only observational techniques can answer. The number of shoppers who enter a store on a given day, the image or copy that catches visitors’ eyes first on a web page, or what products children are most interested in simply can’t be answered by surveys or interviews.

- In other forms of primary market research, you run the risk of question bias (when the wording of questions leads a respondent to answer in a particular way), courtesy bias (when a respondent is reluctant to give negative feedback out of concern for offending the interviewer), or group dynamic bias (when participants respond the way the majority responds, rather than the way they really feel). These typically aren’t issues in observational research.

- Whereas other primary research methods (focus groups, for instance) will only get you a representative sample of your target market, many observational techniques (analytics, heatmapping, keyword research, in-store cameras) will get you data on a much larger census. This eliminates both sampling error and sampling bias.

Disadvantages of Observational Research:

- While observation can tell you volumes about behaviour, it has little to say about those crucial—but unobservable—matters such as attitudes, motivations, intentions, and awareness (the “why”). You’ll need direct contact with your subjects to get those answers.

- Because they can’t discern motives or attitudes based on outward behaviour, observational researchers are often left to make subjective inferences on behaviour that is ultimately difficult to interpret. Not only can this invite researcher bias (subconscious judgments on demographics, for example); it also leaves room for erroneous assumptions about cause-and-effect.

- In many forms of observational research (in-store observation or website analytics, for example), researchers don’t have any control over environments, context, or even subject presence. They must patiently let consumer behaviour unfold as slowly as it does—whenever they finally walk into the store or land on the website—which makes it a potentially time-consuming endeavour with long periods of inactivity.

- Observational research is often limited to discrete activities (shopping for a cereal or looking at a web page); and it can’t take the entire context—let alone the entire activity—into account. (Of course, taking a hybrid approach and pairing observational research with an interview can correct this.)

- It’s limited to research on products, services, apps, etc. that already exist. In other words, observational research won’t let you research what hasn’t happened yet… which means it can’t offer intelligence on the “What if?” questions.

- It brings up a whole set of questions about ethics. The definition of “ethical” is likely to keep evolving over the years—especially as more and more technologies are capable of generating and collecting big data. Consumers feel less and less protected as time goes on; and you’ll want to be sure you don’t blur the line between research and privacy infringement. Under GDPR, there are legal repercussions to consider… but also ask yourself if you’d want to be asked permission if you were in the consumer’s shoes.

As you may have noted, observational research often works best when paired with other market research methodologies. Observation might give you insights into actual consumer behaviour in real-world situations, but a focus group might fill in the thought processes behind the behaviour. Between the two, you’ll have a more complete picture of the consumer’s experience.

Examples of Observational Research

What follows is hardly an exhaustive list: There are probably more observational techniques out there than we’re even aware of. Our goal here is simply to give you a sense of the range of types of observational research out there… maybe some of them will resonate with the questions you’re asking about your business right now.

In-store observation

In-store observation is quite possibly the oldest form of observational research. You can perform it in your own brick-and-mortar store, or in your competitors’ stores. How many people enter the store in a given time period? Are they drawn to something in the window display or were they already clearly intent on entering? How do they get their bearings once they’re inside? What do they notice and where do they go first? How many products do they pick up; how long do they scrutinise the packaging; and what do they ultimately purchase, if anything? What are the demographic characteristics of those who do buy?

The answers can be arrived at via human observation (mystery shoppers or your own employees), mechanical observation (video cameras, electronic checkout scanners, etc), or observational research tools such as footfall counters or frequent shopper cards that gather data about the types of purchases made by certain demographics.

Some businesses even conduct “shop-alongs,” which combine observational techniques and traditional market research: The researcher follows the consumer around the store, and the consumer describes the reasoning behind their purchasing behaviour in the moment, or after purchases are made.

Contextual inquiry

Contextual inquiry is just what it sounds like: inquiring into a consumer’s behaviours or experiences in the context of where those behaviours or experiences take place. Shop-alongs are certainly one form of contextual inquiry; but in-home, in-car, and in-office observation are other “natural environments” were consumers can be observed. What are the pain points in their morning routines? In using certain kitchen appliances? What products are in their laundry rooms? How do they actually use that cleaning product, or implement that business process? (Note that contextual inquiry is typically a hybrid research form.)

These are more intrusive observational techniques, for sure; and they fall under the category of “ethnographic research” (a method popularised by anthropology but widely used in marketing). But they’ll help you identify needs and beliefs that consumers don’t recognise themselves, or that go unarticulated because they don’t know how to verbalise them.

Eye tracking, heatmapping, and scrollmapping

Now we’re talking a different kind of “observational” research altogether: These are all forms of “observing the observer.” Eye-tracking is a technology that detects where an observer’s pupil is by reflecting near-infrared light off the retina. It follows a viewer’s gaze (on a webpage or an advertisement, for example), giving the business a better sense of where visual attention is drawn—and thus, how that website or ad could be optimised.

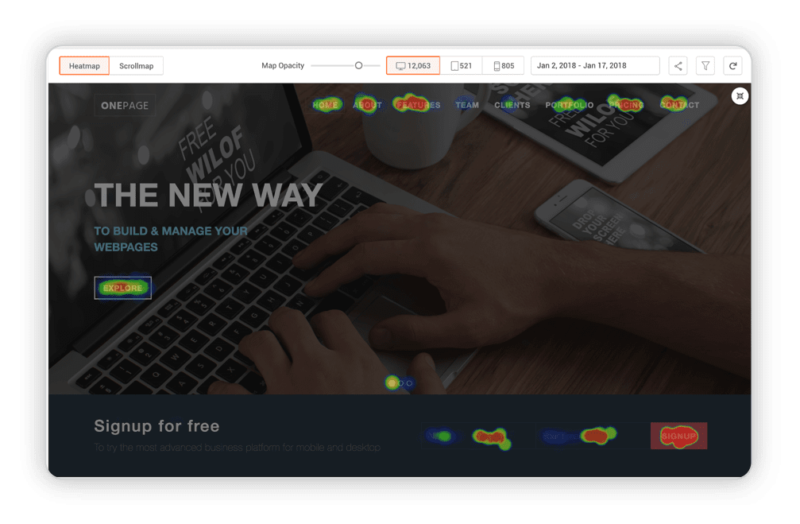

The technology creates a heatmap: a graphical representation of where users most often look. (Heatmaps can also show where website users most often click.) Here’s an example from Zoho PageSense:

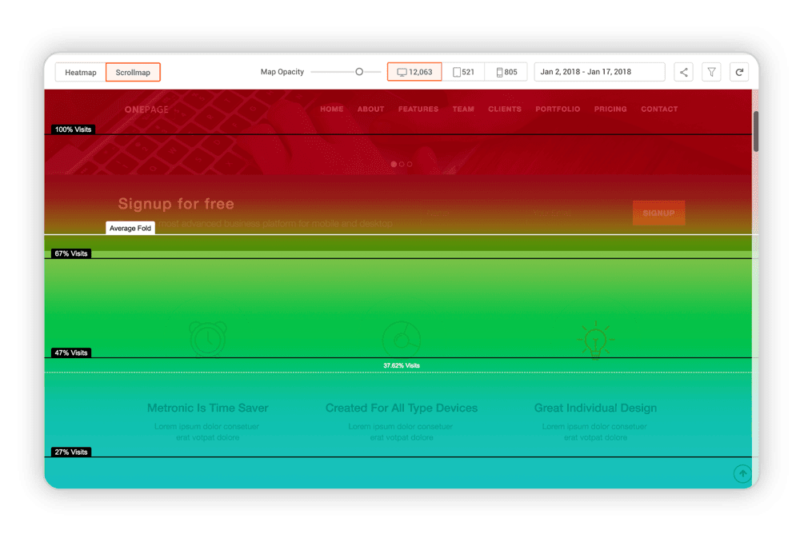

Further observational research along these lines comes in the form of scrollmapping, which allows you to see both how far down the page your visitors tend to scroll (helping you determine, for example, if your blog posts are too long), and what parts of the page they spend the most time on:

Further observational research along these lines comes in the form of scrollmapping, which allows you to see both how far down the page your visitors tend to scroll (helping you determine, for example, if your blog posts are too long), and what parts of the page they spend the most time on:

These observational technologies will help you evaluate the digital content on websites, mobile apps, ads, and more.

These observational technologies will help you evaluate the digital content on websites, mobile apps, ads, and more.

Usability testing

Usability testing encompasses a series of methods of gathering feedback about the ways consumers use your products (or your app, or your website, etc). One form of usability testing is watching a consumer use a prototype of your device. Another is asking subjects to complete a task on your website or app while you watch, listen, and take notes on their spoken thought processes.

The point is to discover if your offering is intuitive enough that users don’t have to call your business for help navigating your website, or resort to a user manual. (Unless your product is complex enough that they need one… in which case, test your manual!) How satisfying is the user experience? Where are the usability hiccups; where could you make the experience smoother; how could you better encourage desired behaviours (getting them to click that “Purchase” CTA, for example)? UserTesting and UsabilityHub are places to turn for such feedback… or maybe you’ve got a group of willing consumers already ready to help you out.

Trace analyses

A “trace” is any residual physical evidence of past consumer behaviour. (Traces always deal in the past). Many of these traces will yield data for your marketing research efforts. These include:

- credit card and sales records

- wear and tear of physical spaces (i.e. tile erosion or carpet wear will indicate customer footfall)

- garbology (purchase patterns can be detected by a glance through the trash)

- cookie data (web users also leave “traces” behind; researchers can analyse browsing history for deeper insights)

Social intelligence

Social listening, too, is “observation”; and it gives you qualitative insights on a quantitative scale. 2.34 billion people worldwide have a social media profile, and many of them are using their profiles to reflect their lives (and their opinions!); so consumer insights and behaviour can be uncovered if you’ve got the right tools. Indeed, social media may be one of the most powerful resources available for modern market research.

Of course, social platforms can be used to pose questions, post surveys, and have public conversations with your target market. But it’s also useful for strictly observational research… in which you simply “listen,” without interacting. Intent to purchase, sentiment analysis (how consumers in different demographics feel about your brand), and campaign analysis can all be deduced through listening. You’ll learn what’s getting liked, what’s getting shared, and who is influencing your target market to have the opinions they have.

Joining a Facebook group in your industry will allow you to “observe” by reading through the group feed. What’s more, there are a wide array of tools out there—including Mention, Social Mention, and Google Alerts—that let you set alerts for certain keywords, such as your business or your product. The platform will notify you every time it uncovers a new mention online… so you only have to do the work of analysing what that mention might mean for your business.

Q&A sites

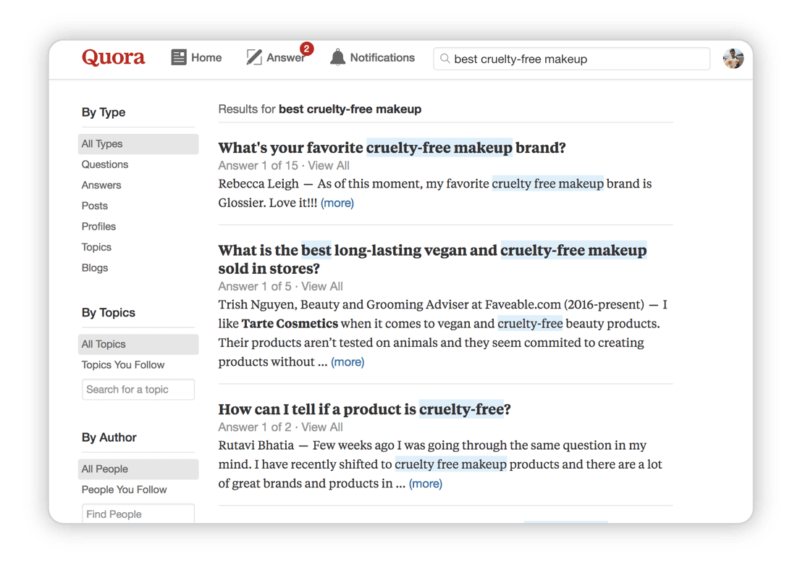

Quora, Reddit, and Yahoo! Answers are all substantial online forums that can provide a wealth of consumer behaviour. (Free questions from your target market? Yes, please!) You can search these, too, for your product or brand name… though if you’re using some of the tools we mentioned above (Mention and Google Alerts search beyond social media platforms) they’ll catch these mentions for you.

Quora, for example, will notify you when questions have been tagged with the topics you select when you set up your profile. And because it organises answers based on “upvotes,” you’ll be able to see which answers users think are most valuable (as well as which questions have been most often answered):

You can also conduct broader search queries on these platforms: What are the pain points people out there are complaining about (the ones you could solve)? What is your target market interested in learning (the stuff you could teach them on your business blog)? What’s the sentiment around your competitors’ offerings? What frustrates or pleases them about the currently-available solutions to their problems?

Keyword research

Consumers’ browsing habits will alert you to their pain points, interests, and concerns. What’s more, keyword research helps you discover the language consumers use to talk about those pain points, interests, and concerns. Google offers both autocomplete suggestions and “Searches related to” at the bottom of every SERP; pay attention to these, because they’re the terms most often used or currently trending.

Other keyword tools include Ubersuggest, Google Trends, and WordStream’s Free Keyword Tools. Each offers different forms of intelligence—search volume, related keywords, average cost per click, tracking of keywords based on distinct criteria, and more. You can generate keyword performance reports as well as lists of keywords specific demographics search for. In other words, keyword research isn’t just for SEO: It’s a market research strategy in and of itself.

Analytics

We’d be remiss if we didn’t include analytics here. The biggest tool in this toolbox, of course, is Google Analytics, which can offer remarkable insights into your market based on how they engage with your website: where visitors are coming from (this is called “referral traffic”), what page they’re first landing on, which pages or blog posts they spend the most time on, and which have the highest exit rate. Analytics will “observe” your market for you, helping you better optimise your virtual offerings in the long run.

You can also combine website tracking with marketing automation, which tracks email engagement (open rates, link clicks, forwards, replies), so you can adjust future email marketing campaigns accordingly.

A third analytics strategy—for use on both your website and your email marketing campaigns—is A/B testing. You’ll develop two different versions of a web page or email, with a single variation between the two (a different headline or call to action, for example). A portion of your visitors or recipients will get one version and the rest will get the other version; the software tracks the two and determines which version is most effective. A/B testing will help you make small, incremental refinements that will ultimately make a big difference. In general, analytics allows you to go from insight to action pretty quickly.

There are plenty of observational techniques we didn’t cover here—tracking software for devices and content analyses are two that come to mind—and the next new technology may be available by the time this page goes live. (We’ll keep you updated, of course.) Each method above will add value to your market research in different ways; and if you couple them with surveys, focus groups, competitor research and other forms of secondary market research, you’ll have a wealth of information at your fingertips to improve every aspect of your business—for both yourself and your target market.

Related Articles

Conducting Primary Market Research

If you’ve been following along with us on this market research journey, you’ve already conducted a situation analysis to determine your business’s market research question. You’ve also begun conducting competitor research and looking into other forms ...Best Practices for Moderating and Analysing Interviews and Focus Groups

Deciding which method of primary research is the best strategy for your market research question is big enough to be its own topic. In the last section, we offered recommendations for choosing whether to conduct an in-depth interview or a focus ...Creating a Killer Market Research Survey

Sometimes the best way to discover what your target market really thinks of your business is simply to ask it. If you’ve been in business for more than a couple of hours, you know that consumers have strong opinions. Offering a market research survey ...Introduction to Market Research: When and How to Start

Welcome back to our introduction to market research! As you probably remember, we first introduced the idea of market research by comparing it to solving a mystery. Though the end results are different (we imagine your market research won’t conclude ...Resource List for Secondary Market Research

While it won’t give you specific answers or intelligence about your business, secondary market research is critical to running a successful organisation. Unlike primary research, this type of research is conducted through sources who’ve already ...